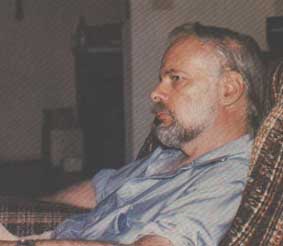

| Philip K. Dick  AKA Philip Kindred Dick AKA Philip Kindred Dick

Born: 16-Dec-1928

Birthplace: Chicago, IL

Died: 2-Mar-1982

Location of death: Santa Ana, CA

Cause of death: Heart Failure

Remains: Buried, Riverside Cemetery, Fort Morgan, CO

Gender: Male

Religion: Anglican/Episcopalian [1]

Race or Ethnicity: White

Sexual orientation: Straight

Occupation: Novelist Nationality: United States

Executive summary: Blade Runner Born December 16, 1928 in Chicago, Illinois, science fiction author Philip Kindred Dick started off his life with the same disturbing, high-intensity noir eeriness that would later mark his novels and short fiction. Born in a set of twins, Dick was tragically separated from his other half after a mere eight weeks when she died from an (alleged) allergy to her mother's milk. Dick bitterly blamed his mother for the bizarre development, and his lingering suspicion about the way his twin dwindled from the world of the living would leave a deep wound that he carried for the rest of his life. His parents split up when he was quite young, and he was subsequently uprooted and relocated with his mother to Berkeley, California -- where he would remain for much of his life.

Dick's debut as a published author came in 1952 with a short story entitled "Roog". In 1955 he published Solar Lottery, his first novel. The early 50s and 60s were an incredibly prolific period for him. He produced roughly a hundred short stories and two dozen or so novels during this era, including Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (1965), Time Out Of Joint (1959), and the Hugo Award winning The Man In The High Castle (1962).

Although awarded both the Hugo and the John W. Campbell Memorial Awards (for Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said, 1974), Philip K. Dick also holds the more unusual distinction, among science fiction writers, of having achieved greater fame and fortune posthumously than while living. Dick was on the cusp of his success in 1982 when he died of a heart attack, following a stroke. Shortly afterward, Ridley Scott's Blade Runner debuted, featuring rising star Harrison Ford. Based on Dick's Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, the film was only a mild success, but it heralded the beginning of the wealth and mass appeal that had eluded Dick throughout his career.

Dick's popularity exploded in 1990 when Arnold Schwarzenegger starred (and finagled into being) the blockbuster smash Total Recall. Based on Dick's "We Can Remember It for You Wholesale", the action adventure extravaganza grossed $118 million in the U.S. alone. Since then, Hollywood has beaten a path to Dick's estate manager, optioning so many PKD stories and novels that complex charts are needed to keep track of which ones are optioned and which in production and which are soon to be released.

Consequently Dick is, at present, the most adapted SF author in the history of film. Hollywood treatments of his work include: Screamers, starring Peter Weller (1995); Minority Report, with Tom Cruise (2002); Imposter starring Gary Sinise (2002); and Paycheck, a John Woo film featuring Ben Affleck and Uma Thurman (2003). Most of the films are but loose adaptations of Dick's work. A Scanner Darkly, directed by Richard Linklater and starring Keanu Reeves and Winona Ryder, was the first Dick adaptation film to remain generally true to the original novel.

But while these films have proved a boon to Dick's heirs (two daughters and a son, by three of his five marriages), Dick himself never experienced such glamour. Writing like a man possessed, he was ever haunted by the specter of poverty, receiving little payment for his 150 short stories and 36 novels. The need for cash, and the availability of cheap speed, fueled his incredible productivity. In one year alone he produced roughly 30 stories for science fiction pulp magazines like Astounding and Amazing, generally powering through his stories at the rate of 80 to 100 words per minute. Dick said of himself, "The words come out of my hands, not my brain," and, "I write with my hands."

But the manner of his work and his heavy addiction to drugs took their toll. He sometimes collapsed at the end of a project. He burned through five marriages, some in less than a year. And over time his psyche began to match the paranoid, anxious profile of a speed tweaker. Then in 1974 he had what he sometimes later feared was a schizophrenic breakdown -- although he was fairly sure that it was really a profound religious experience. The experience itself permeates all of his later novels, most notably in Valis (short for Vast Active Living Intelligence System) in which a godlike extraterrestrial computerized guardian watches over mankind, seeking to subtly influence them in life-positive directions. Like the Chinese "Tao", it often succeeds most adroitly with small children and apparent crazies -- like drug addled science fiction writers.

Notably, much of Dick's work is characterized by the recurrent theme of gnostic deception and false realities, of the humble protagonist who accidentally discovers that the perception he took for granted is in fact a delusion. In Valis it is discovered that, in addition to our satellite A.I. guardian, humankind must contend with the negative influence of the "Empire that never ended". The Roman Empire, we discover, was but one temporal manifestation of a deeper force that intrudes into our world through various places in time, seeking to imprison us in a reality of suffering, hatred, and violence. Dick repetitively states, "The Empire never ended," showing us its dark face behind the mask of new forms of social control.

The Empire's darkness also shows up in individuals who become so cut off from their humanity that they unwittingly serve the Empire (or the Black Iron Prison). Dick meanwhile frequently serves up ironic contrast by showing us machine characters, like android Garson Poole ("The Electric Ant") and the automatic cabbie in Now Wait for Last Year, who exude kindness, social responsibility, and other pro-social characteristics.

Dick's view of the universe was unusual and certainly unsettling -- false realities, frightening pursuits, insidious forces at work behind the scenes, themes of confusion and decay, and protagonists forced to work out their own theory of salvation, or at least of well-informed right action. Yet it is precisely all of this that makes him so worthy of the nearly universal acclaim he accrued within the science fiction community. Dick's work makes one ask what if, but in a way that questions fundamental assumptions of that which is generally taken for granted: the here and now. Dick represented the "speculative science" of science fiction taken to a profound level. At the same time, the inherent drama behind his stories -- of characters struggling to find their place and security in a world that baffles and sometimes terrifies -- speaks to a intense variety of the human experience, one that more and more readers and moviegoers seem to identify with in the 21st century.

[1] Interview, Slash magazine, May 1980: "Technically, I'm Episcopalian, but I don't ever go. I'm interested in them because they're a barrio church and they do lot of civil service work... technically I'm a religious anarchist."

Sister: Jane (his twin, d. age 6 weeks)

Wife: Jeanette Marlin (m. 1948, div. 1948)

Wife: Kleo Apostolides (m. 1950, div. 1958)

Wife: Anne Williams Rubinstein (m. 1958, div. 1964, one child )

Wife: Nancy Hackett (m. 1966, div. 1970, one child)

Wife: Tessa Busby (m. 1973, one child)

Daughter: Isa (b. 1967)

Son: Christopher

High School: Berkeley High School, Berkeley, CA (1946)

Hugo

unknown detox facility

Stroke

Suicide Attempt multiple

Heart Attack

Died Intestate

Risk Factors: Schizophrenia, Asthma, Agoraphobia, Amphetamines, Depression, LSD

Official Website:

http://www.philipkdick.com/

Rotten Library Page:

Philip K Dick

Author of books:

Solar Lottery (1955)

The Man Who Japed (1956)

The World Jones Made (1956)

The Cosmic Puppets (1957)

Eye in the Sky (1957)

Time Out of Joint (1959)

Dr. Futurity (1960)

Vulcan's Hammer (1960)

The Man in the High Castle (1962)

The Game-Players of Titan (1963)

Clans of the Alphane Moon (1964)

Martian Time-Slip (1964)

The Penultimate Truth (1964)

The Simulacra (1964)

The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (1965)

The Unteleported Man (1964)

Dr Bloodmoney -- or How We Got Along After the Bomb (1965)

The Crack in Space (1966)

Now Wait for Last Year (1966)

Counter-Clock World (1967)

The Ganymede Takeover (1967, with Ray Nelson)

The Zap Gun (1967)

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (1968)

Galactic Pot-Healer (1969)

Ubik (1969)

We Can Build You (1969)

A Maze of Death (1970)

Our Friends from Frolix 8 (1970)

Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said (1974)

Deus Irae (1976, with Roger Zelazny)

A Scanner Darkly (1977)

In Milton Lumky Territory (1984, posthumous)

Lies, Inc. (1984, posthumous)

Man Whose Teeth Were All Exactly Alike (1985, posthumous)

Puttering About in a Small Land (1985, posthumous)

Radio Free Albemuth (1985, posthumous)

Humpty Dumpty in Oakland (1986, posthumous)

Mary and the Giant (1987, posthumous)

The Broken Bubble (1988, posthumous)

The Dark-Haired Girl (1988, posthumous)

Nick and the Glimmung (1988, posthumous)

In Pursuit of Valis (1991, posthumous)

Cantata 140 (2003, posthumous)

The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick (2010, posthumous)

Do you know something we don't?

Submit a correction or make a comment about this profile

Copyright ©2019 Soylent Communications

|